Yellow Express Heavy Haulage from the 1960s

Throughout the late forties and on through the sixties, with depots scattered over the length and breadth of the country, Yellow Express trucks hauled parcel freight, interstate general loads and were specialists in heavy haulage. Yellow Express were one of the most dynamic emerging transport companies in Australia before they were engulfed by the Main Nickless Organization in the seventies.

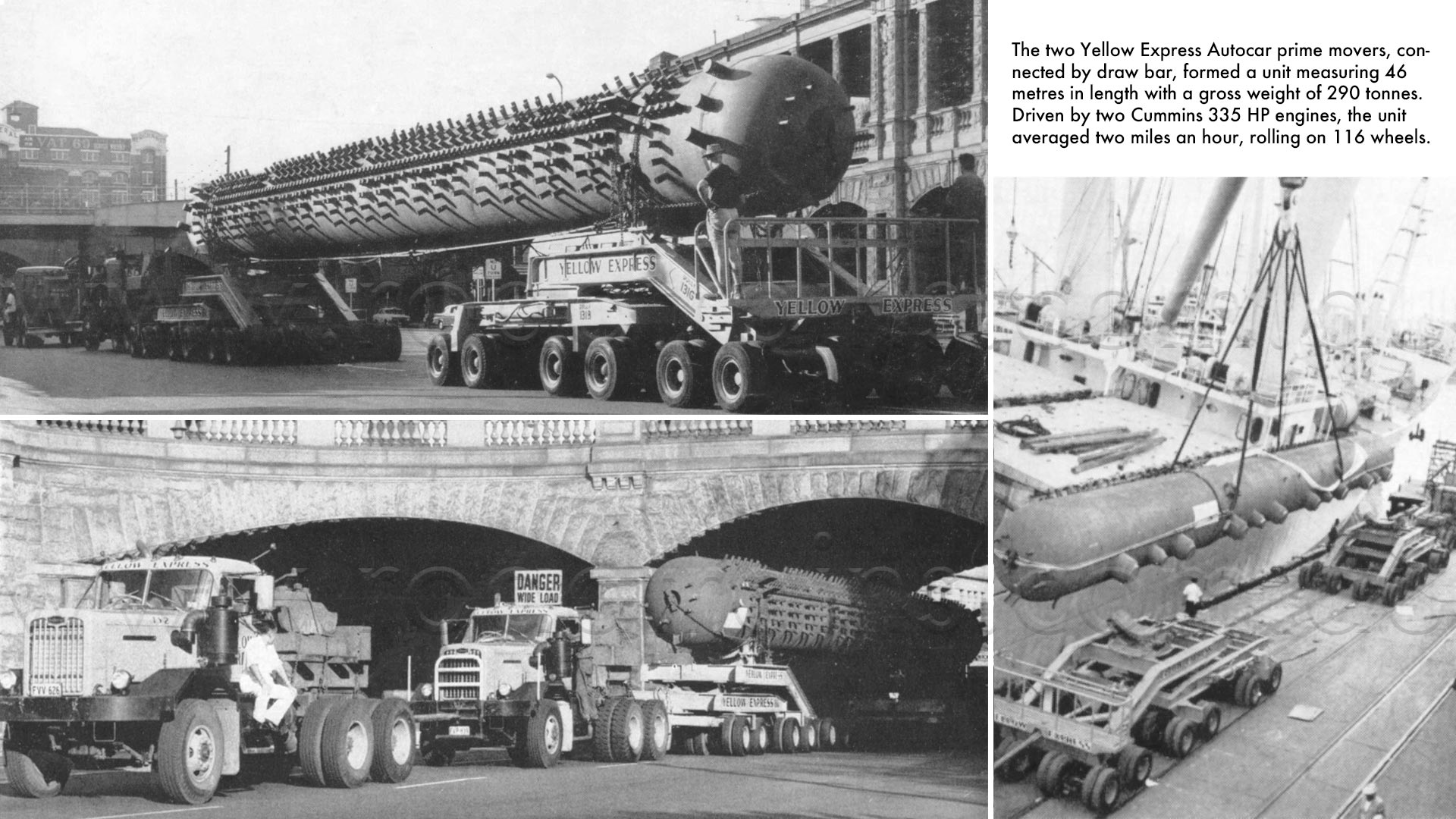

Yellow Express 206 tonne by 26 meter boiler for Liddell Power house

It was 26 metres long, weighed in at 206 tonnes and rewrote the pages of Australian transport history. Even by today’s standards, it was a bloody big shift. It was during the early sixties; unemployment was low and the post WW2 boom was in full swing. Yellow Express already held the record for the heaviest indivisible payload ever carried in Australia, now they had to add some 30 tonnes to the figures in the record book when they carried this imported boiler on the closing stages of a 10,000 mile (16,0094 km) journey to Liddell Power house.

A Painters and Dockers’ strike almost resulted in the boiler being left aboard the freighter that shipped it to Australia from Norway. This would have meant that the boiler’s next point of call would have been Japan. Wharfies and crew of an Australian ship saved the situation.

The Norwegian freighter, ‘Arna’ was berthed next to the ‘Australia Star’ whose giant 300 tonne capacity crane was used to unload the monster load. The boiler wasn’t unloaded on the first attempt, as it slipped the chocks. The wharfies and ship’s crew finally had it off the ship and loaded on top of the Yellow Express heavy haulage unit the following day. The boiler’s eight-mile trip from the wharves at Glebe to Cook’s River railway yards took 32 hours. The two Yellow Express Autocar prime movers, connected by draw bar, formed a unit measuring 46 metres in length with a gross weight of 290 tonnes. Driven by two Cummins 335 HP engines, the unit averaged two miles an hour, rolling on 116 wheels. The last stage of the journey, from Cook’s River to the Electricity Commission’s Liddell Power house was made by rail.

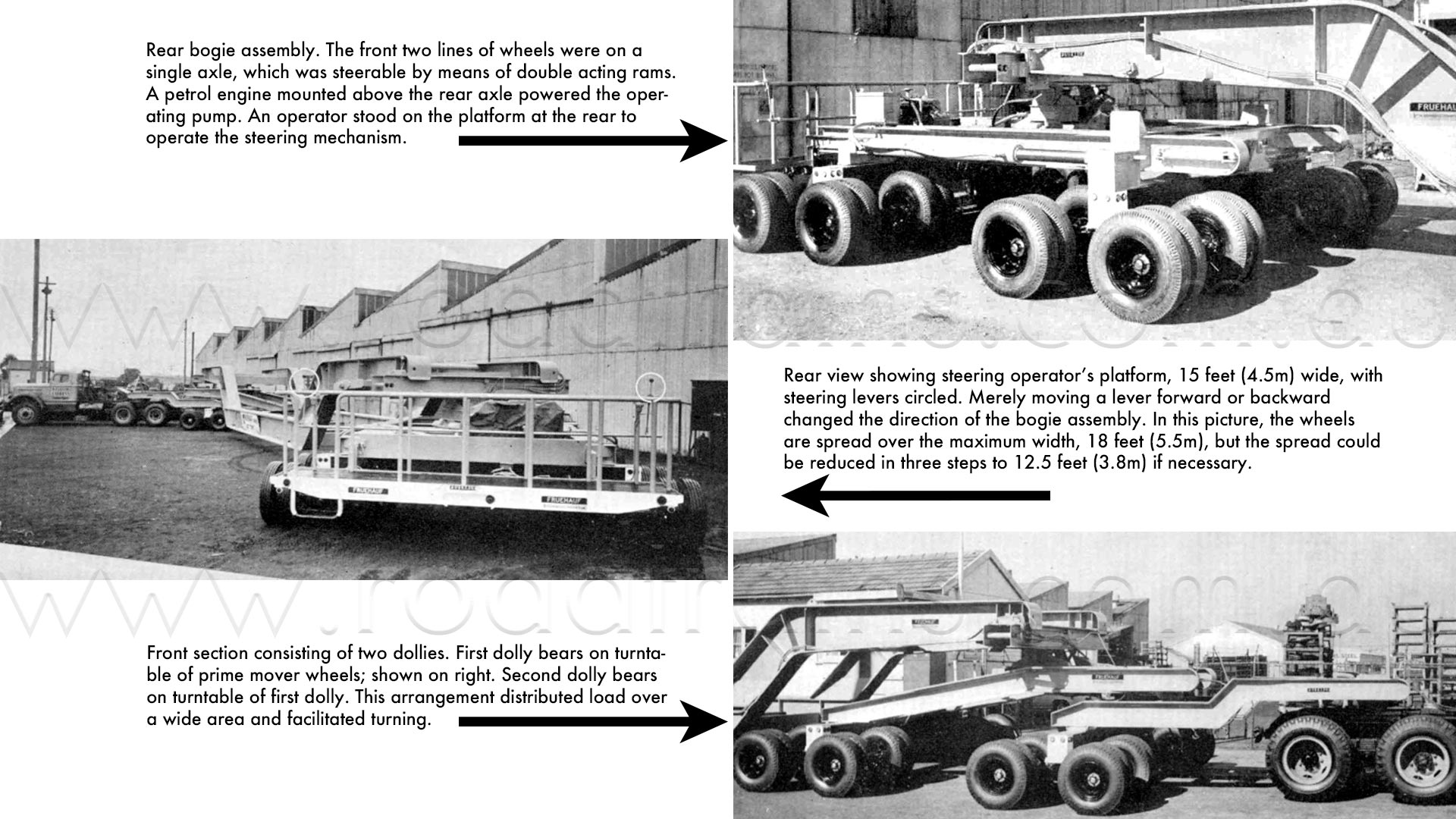

The overall length was 102 feet (31 m) and the total tare weight was 50 tonnes.

Top Right image above: Rear bogie assembly. The front two lines of wheels were on a single axle, which was steerable by means of double acting rams. A petrol engine mounted above the rear axle powered the operating pump. An operator stood on the platform at the rear to operate the steering mechanism.

Middle Left image above: Rear view showing steering operator’s platform, 15 feet (4.5m) wide, with steering levers circled. Merely moving a lever forward or backward changed the direction of the bogie assembly. In this picture, the wheels are spread over the maximum width, 18 feet (5.5m), but the spread could be reduced in three steps to 12.5 feet (3.8m) if necessary.

Bottom Right image above: Front section consisting of two dollies. First dolly bears on turntable of prime mover wheels; shown on right. Second dolly bears on turntable of first dolly. This arrangement distributed load over a wide area and facilitated turning.

Tight Cornering

During the early sixties the growing weight of indivisible loads such as electrical transformers and generators, sections of presses, drop hammers and refinery plant, created the need to have a trailer combination capable of carrying a load of 100 tonnes, so the unit shown here was added to the Melbourne fleet.

With one prime mover attached, the overall length was 102 feet (31 m) and the total tare weight was 50 tonnes. The combination was fitted with 74 tyres with an average loading of about 2 tonnes per tyre when a payload of 100 tonnes was imposed.

The vehicle had been designed to meet requirements of road authorities under controlled conditions. The spread of wheels on the axles of the trailers could be varied between an outside width of 18 feet (5.5m) and 12.5 feet (3.8m), in this latter position the wheels were equally spaced laterally. The spread of wheels added complexities to construction and operation, but was necessary to distribute the heavy loads over roads and bridges, particularly the latter.

The rear bogie assembly could be steered permitting the combination to make a 360-degree turn with a radius of about 50 feet (15m). This enabled a right angle turn to be made in a single movement at most street corners. On straight roads the mechanism could be locked in a straight position.

Braking was applied to each set of dual tyres by compressed air actuating mechanical brakes. All brakes were controlled by the driver of the prime mover, or in an emergency, by the operator on the rear platform.

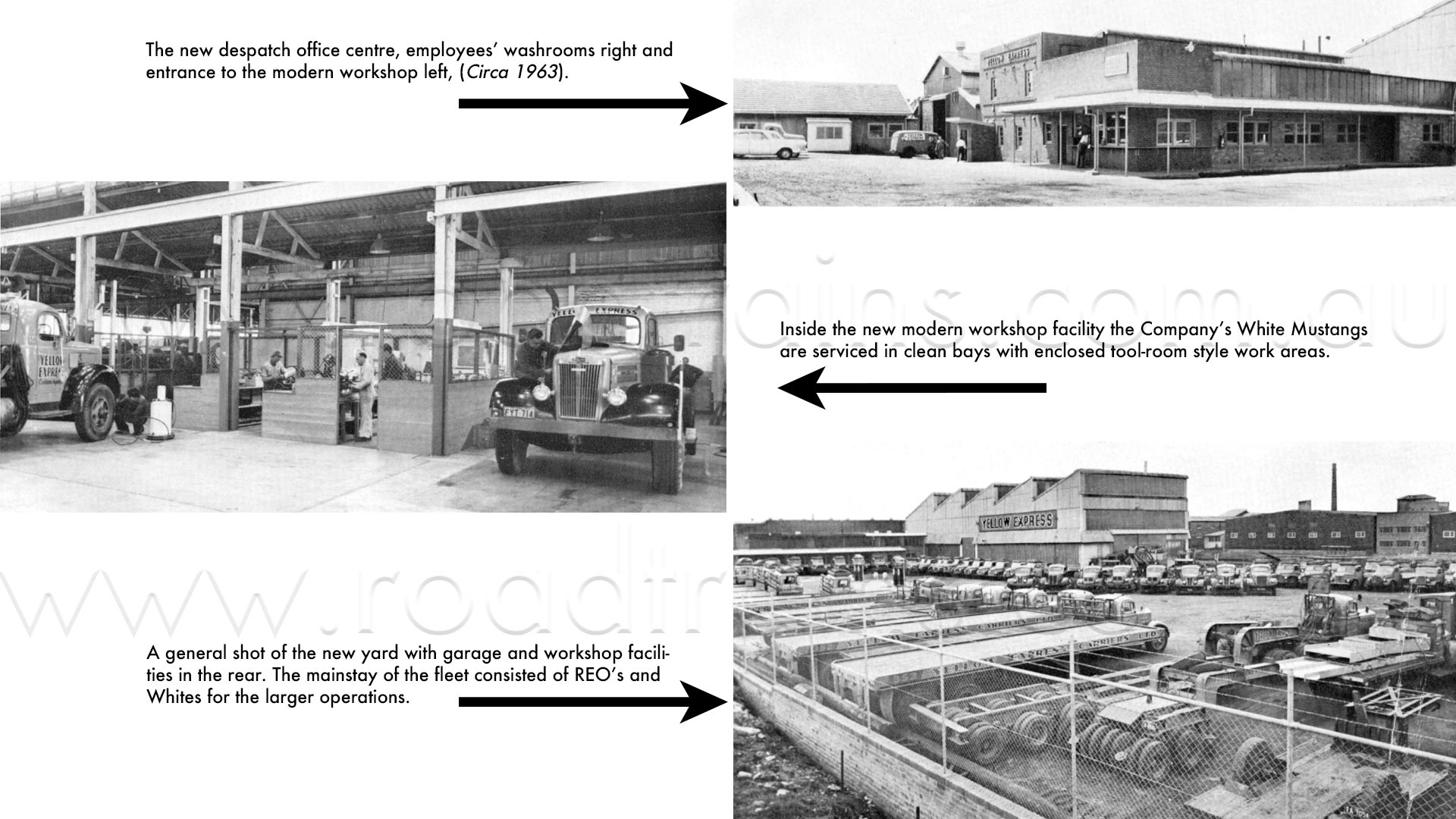

Yellow Express heavy haulage devision moved in to new facilities at Alexandria in 1963

Expansions

1963 and Yellow Express’ interstate general and parcel business were in full swing. Intermodal transport between capital cities and regional areas was growing at a rapid rate. For many years the company’s premises in Pyrmont, Sydney had provided accommodation for offices, garaging, workshop and depot facilities for all its diversified activities in the Sydney area. Demand for space had been steadily increasing until it reached a point where the eventual uneconomic congestion created an urgent need for additional space.

The probable need had been foreseen in 1946 when 1.5 acres (0.6 hectare) of land nearby was purchased and held in reserve. Subsequently, however, this land became zoned unsuitable for the company’s needs and a search was made elsewhere for an area to supplement the space at Pyrmont. Towards the end of ‘62 the Company purchased an area of approximately 2.5 acres (1 hectare) in Burrows Road, Alexandria and the existing buildings on this were improved and extended to meet the Company’s requirements. To this area the General Cartage, Heavy Haulage and Crane sections transferred, together with maintenance, workshop plant and personnel.

This move not only eased the burden on the operation of the transferred sections of the Company’s business, but also gave more working space for the parcel delivery, interstate forwarding, payment roll delivery and Customs Agency sections that remained at Pyrmont. The Sydney administrative offices remained at Pyrmont.

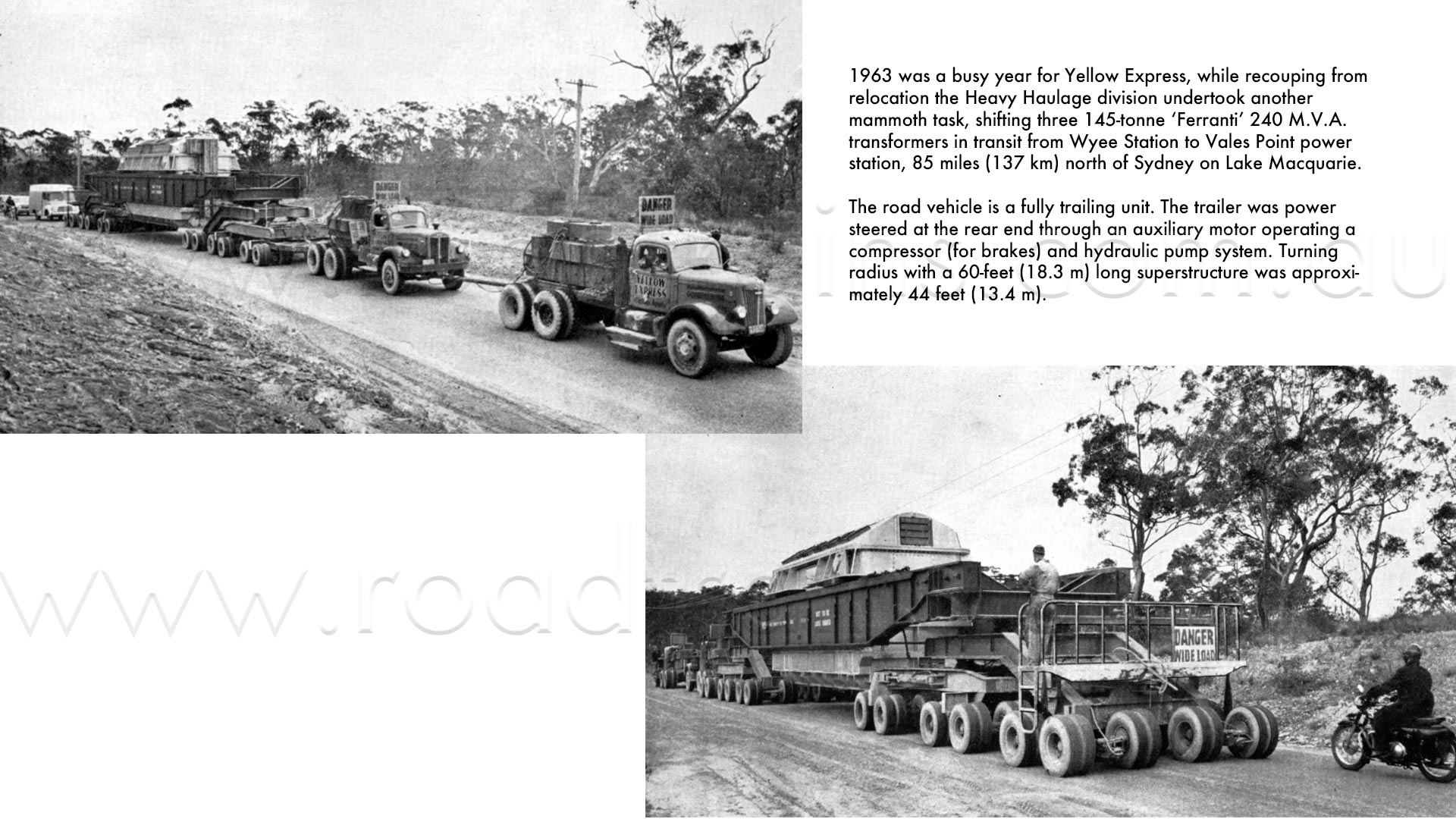

1963 – shifting three 145-tonne ‘Ferranti’ 240 M.V.A. transformers in transit from Wyee Station to Vales Point power station, 85 miles (137 km) north of Sydney on Lake Macquarie.

Road Train with a Difference

1963 was a busy year for Yellow Express, while recouping from relocation the Heavy Haulage division undertook another mammoth task, shifting three 145-tonne ‘Ferranti’ 240 M.V.A. transformers in transit from Wyee Station to Vales Point power station, 85 miles (137 km) north of Sydney on Lake Macquarie.

The transformer shown is the second of three and was unloaded from a ship in Sydney by the 150-tonne floating crane and placed in the railways’ 180 tonne capacity transformer wagon at a nearby rail berth.

The load was then taken to Wyee Station (situated about six miles (9.5 km) from the power station) and there transferred to the road vehicle. From Wyee Station the transformer was transported by road to the power station site where it was unloaded, placed on its undercarriage and positioned ready for assembly.

These points are worth noting in connection with this movement:

These transformers were the largest imported into Australia at the time.

For the movement from Wyee to Vales Point the rail bogies were removed from the rail wagon and the road bogies substituted. Coupling of beams to the road bogies was by special adaptors designed and constructed in the Yellow Express workshops. The complete railway wagon superstructure and load was mounted on road wheels and transported to site. Upon completion of unloading, superstructure was re-assembled and returned to Wyee Station and remounted on the rail bogies.

The road vehicle is a fully trailing unit. The trailer was power steered at the rear end through an auxiliary motor operating a compressor (for brakes) and hydraulic pump system. Turning radius with a 60-feet (18.3 m) long superstructure was approximately 44 feet (13.4 m).

Yellow Express had already handled in this manner three similarly large transformers at Vales Point (two ‘Hitachi’ about 140 tonnes each and the first ‘Ferranti’ of which this is the second). They later handled a 310 M.V.A. transformer weighing about 180 tonnes. Several other switching transformers of between 110 and 140 tonnes were transported in the same manner a short time later. Gross weight of the load and trailer without the prime movers was about 200 tonnes.

Travelling time for the 96 tyred full trailing low loader from Wyee to Vales Point, six miles (9.6 km) away was approximately two hours, speed being regulated by traffic conditions on the highway and acute turns. Movement was assisted by the efficient co-operation of the NSW police.

Yellow Express shift Marion dragline in 1965

Big Plans & Bigger Diggers

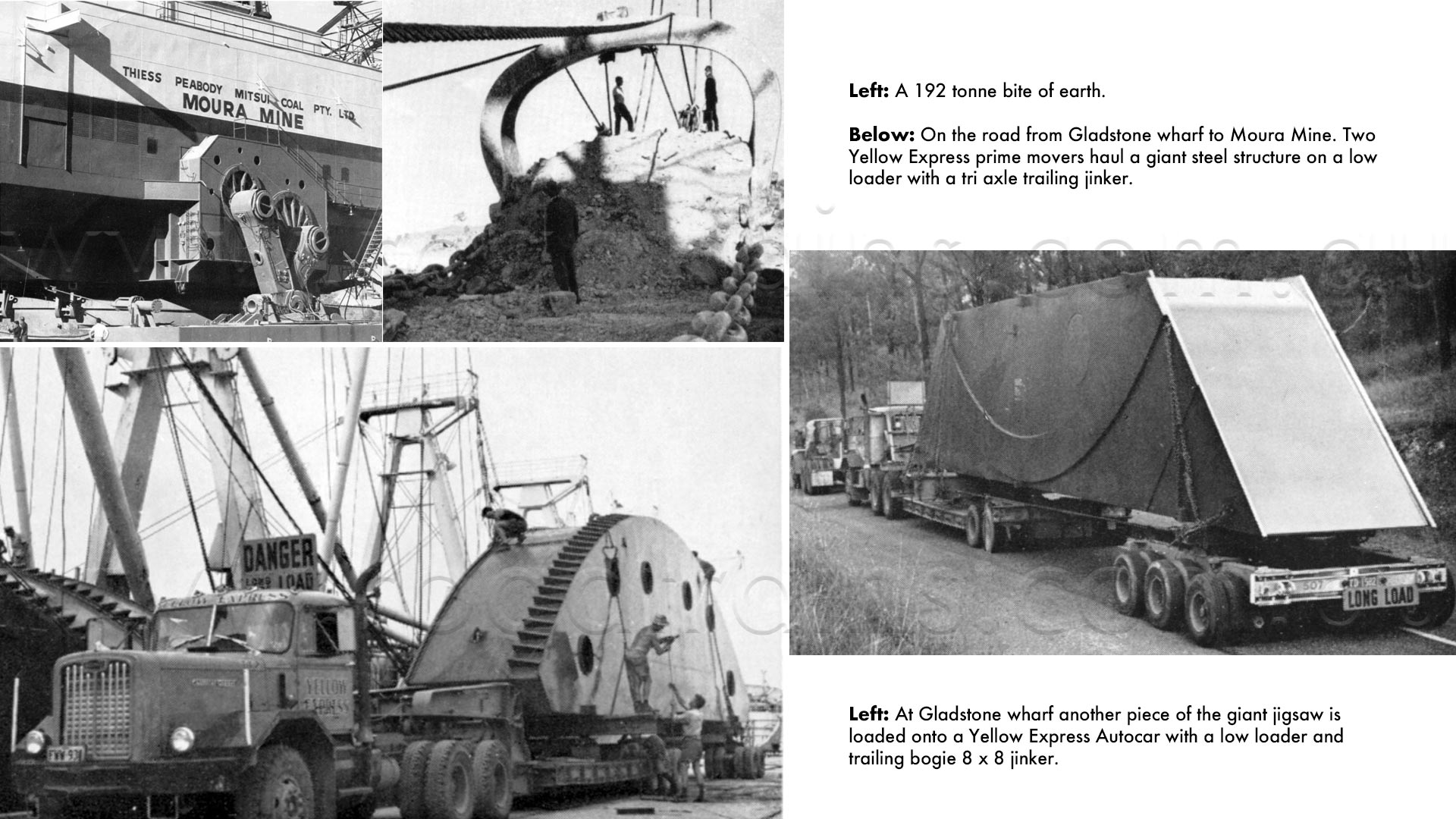

The year was 1965, a time of optimism when the realms of probability were turned into the possible. The Central Queensland coalfields were just being developed and Theiss, Peabody, and Mitsui Coal Pty Ltd had really big plans for their rich mining deposits at Moura.

This was the coal that fired the Japanese economic miracle and demand for the energy source was such that the Moura mine was exporting two million tonnes a year out of the port of Gladstone nearly 200 kilometres away to the east.

Digging up this amount of coal called for a hungry machine – a dragline that could take a 192 tonne bite out of the earth each scoop. The Marion dragline was nothing if not ambitious. It was nearly as big as an ocean liner, and at a massive 6,000 tonnes it just about weighed as much too. Designed and constructed in the USA, the massive bulk of the machine meant that it had to be sent to the Moura mine in a jigsaw of pieces. While it could travel on its own giant walking feet, the dragline’s top speed of 200 metres per hour and sheer bulk would have been something to behold.

There were over one hundred sections that made up the beast, with none that could be described as a standard load. Each was over-dimensional and some weighed as much as 70 tonnes. The job of transporting the mining monster was taken on by Yellow Express who picked up the sections at the Gladstone wharf and transported them onsite at Moura mine.

To correctly assemble the machine the loads had to be delivered in order and at the right location. According to reports at the time the shift went to plan and the machine was digging up coking coal on schedule.

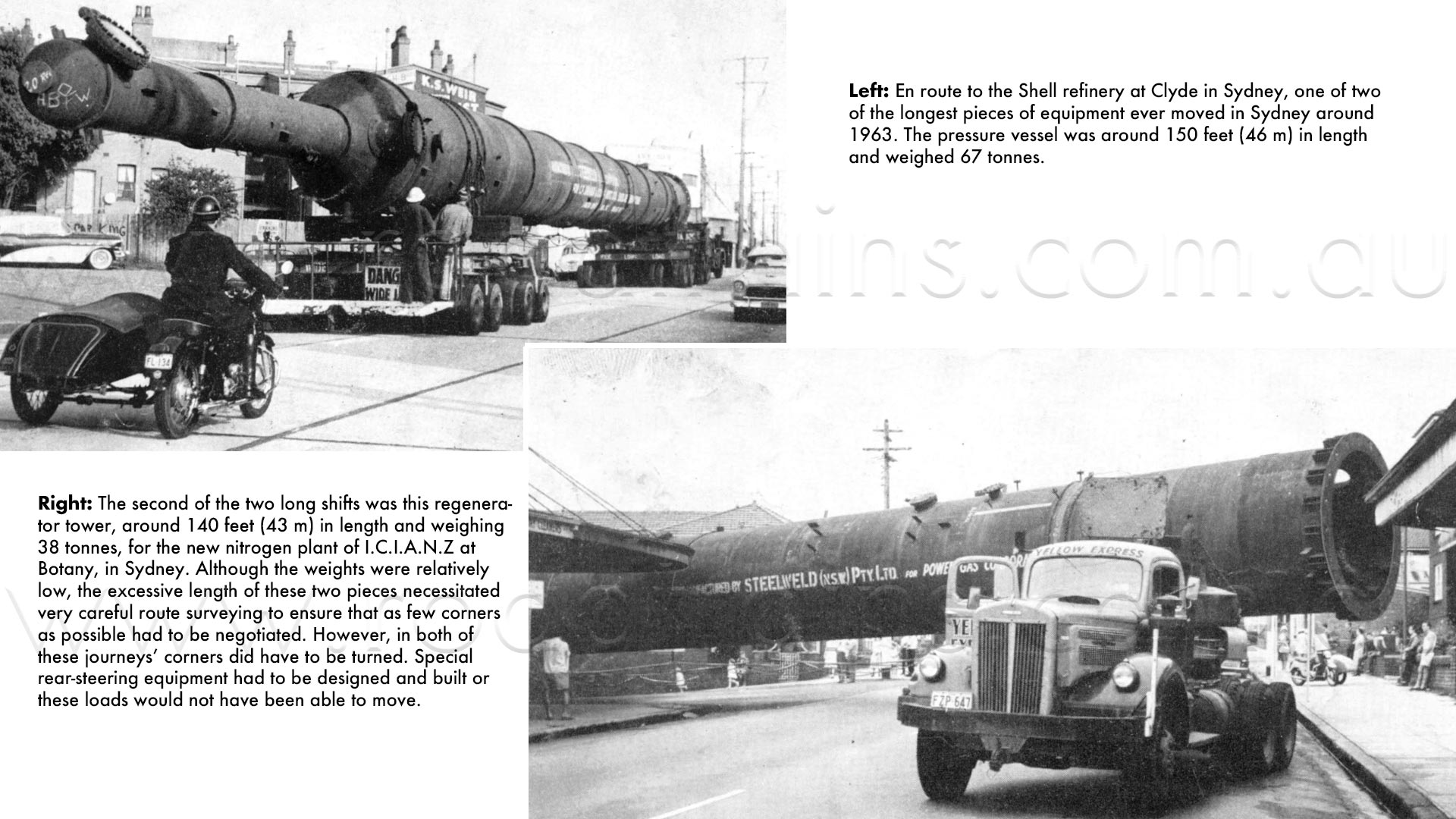

The pressure vessel was around 150 feet (46 m) in length and weighed 67 tonnes.