It is midwinter in Northwest Canada where temperatures can drop to 40 below making it dangerous to leave any patch of skin uncovered. Yet it is only in midwinter when these gargantuan loads can be shifted as Howard Shanks discovered.

At Dacro Industries Ltd in Edmonton, Alberta, it is a little after dark. Half a dozen or so large light towers illuminate the gigantic black steel cylinder, called a ‘Coker’, sitting on top of 350 wheels.

The hard packed snow crunches under every footstep as Chris Waddell, Premay’s Transport Supervisor approaches the group of 50 men and women huddled in a semi circle beside the rear of the Coker.

“Communications with you guys in the pilot cars on the radio tonight keep it short and sweet,” Chris informs.

Premay Heavy Haulage Kenworth

“If we’re ready to roll at one minute to eleven then that’s when we’d like to do it,” Chris says, concluding his first of what’s dubbed a ‘tailgate safety meeting’ with the crew for the night’s shift out of Edmonton.

A move such as the delivery of this Coker from Edmonton to Suncor Energy’s Tar Island plant north of Fort McMurray requires up to two years of planning and scheduling by Premay’s engineering services and logistics team. Premay makes these mammoth moves in the cold of winter when roads freeze hard; spring and summer manoeuvres of that weight would only damage the roads.

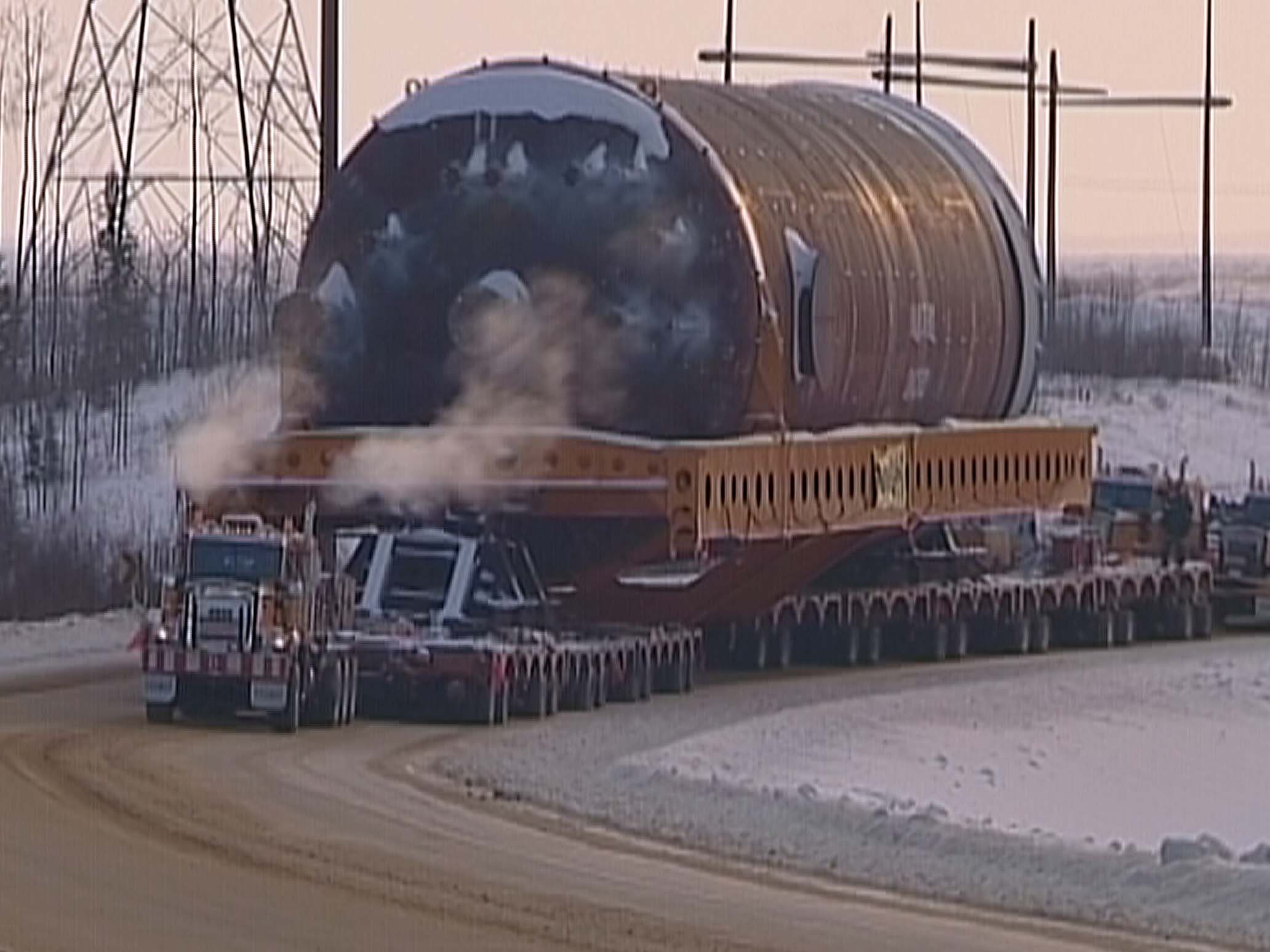

“This Coker is the largest vessel we have moved to date,” Premay’s Len Johnson informed. “It is 31 feet (9.45meters) in diameter and around 132 feet (40.23 Meters) long and weighs 470 metric tonnes. All up with the transport frame and trailers there is about 780 metric tonnes.

It had taken the Premay crew five days to assemble the transport frame around the Coker and place it on the two Scheurle hydraulic platform trailers.

It had taken the Premay crew five days to assemble the transport frame around the Coker and place it on the two Scheurle hydraulic platform trailers.

“The rear trailer has 192 wheels and the lead trailer 160 wheels so we have a total of 352 wheels,” Len Johnson explained. “The main reason for this is to spread the load out on the bridges that we cross.”

Alberta sits on top of the biggest petroleum deposit outside the Arabian Peninsula – as many as 300 billion recoverable barrels and another trillion-plus barrels that could one day be within reach using new retrieval methods. (By contrast, the entire Middle East holds an estimated 685 billion barrels that are recoverable.) But there’s a catch. Alberta’s black gold isn’t the stuff that gushed up from Jed Clampett’s backyard. It’s more like a mix of Silly Putty and coffee grounds – think of the tar patties that stick to the bottom of your sandals at the beach – and it’s trapped beneath hundreds of feet of clay and rock.

As the price of oil creeps ever higher, the petroleum-rich tar sands of northern Alberta grow in importance every day. Wildcatters, (oilmen who drills exploratory wells in territory not known to be an oil field), stake their claim to tap into the heavy, gooey oil locked beneath hundreds of feet of rock and clay. But to unlock this prize, oil company operators need massive extracting and “cooking” equipment like this Coker, but more on that later.

As the price of oil creeps ever higher, the petroleum-rich tar sands of northern Alberta grow in importance every day. Wildcatters, (oilmen who drills exploratory wells in territory not known to be an oil field), stake their claim to tap into the heavy, gooey oil locked beneath hundreds of feet of rock and clay. But to unlock this prize, oil company operators need massive extracting and “cooking” equipment like this Coker, but more on that later.

Heavy oil isn’t a new discovery. Native Americans have used it to caulk their canoes for centuries. Until recently, though, it’s been the energy industry’s stepchild – ugly, dirty, and hard to refine. But the political winds are favouring the heavy stuff, as “energy independence” – aka freedom from relying on Middle East oil – has become a war-on-terror buzz-phrase.

Better yet, recent improvements in mining and extraction techniques have cut heavy oil production costs nearly in half since the 1980s, to about $10 per barrel, with more innovation on the way. The petroleum industry is spending billions on new methods to get at the estimated 6 trillion barrels of heavy oil worldwide – nearly half the earth’s entire oil reserve. Two years ago, Shell and ChevronTexaco jointly opened the $5.7 billion Athabasca Oil Sands Project in Alberta, which pumps out 155,000 barrels per day.

Better yet, recent improvements in mining and extraction techniques have cut heavy oil production costs nearly in half since the 1980s, to about $10 per barrel, with more innovation on the way. The petroleum industry is spending billions on new methods to get at the estimated 6 trillion barrels of heavy oil worldwide – nearly half the earth’s entire oil reserve. Two years ago, Shell and ChevronTexaco jointly opened the $5.7 billion Athabasca Oil Sands Project in Alberta, which pumps out 155,000 barrels per day.

There was a flurry of activity in the Dacro Industries’ depot, a few minutes before the scheduled 11pm departure of the choreographed night move through Edmonton. With every vehicle fitted with revolving orange lights whirling the seven C500 Kenworth prime movers, three pulling and four pushing were ready to roll.

The Caterpillar C15-550 hp engines growled and the drive wheels slowly turned the snow chains creaked as they bit hard in to icy snow and inch-by-inch the Coker began to move.

It would take five hours to get the Coker out of Edmonton, where it would park up till day break. In the cities an advance crew moved ahead of the Coker shifting traffic and street lights, which were quickly replaced by the trailing crew. This was the first of two night moves, the other would be through Fort McMurray designed to ease the inconvenience to the motoring public. All other travel is done during daylight hours.

It would take five hours to get the Coker out of Edmonton, where it would park up till day break. In the cities an advance crew moved ahead of the Coker shifting traffic and street lights, which were quickly replaced by the trailing crew. This was the first of two night moves, the other would be through Fort McMurray designed to ease the inconvenience to the motoring public. All other travel is done during daylight hours.

This is no ordinary truck driving job. Kevin Spreen sits behind the wheel of the lead Kenworth C500, he’s been operating heavy haulage equipment all through the Western Region of Canada for more years than he cares to remember. We asked Kevin what is involved in driving the lead truck.

“I have to keep in communication with my push-trucks at the back, Kevin informs as he glance in the mirror. “ I also have to listen to Darryl Herbert, who controls traffic on the back and he steers the trailer when we have to. And then there is Rick Iverson who is levelling the trailer.”

“It takes everybody to get this down the road it doesn’t just take one,” Kevin adds. “That’s where Premay is good, everybody works as a team and when we all work together it is a little easier all around.”

At the top of Beacon Hill heading into Fort McMurray the crew gathers for another tailgate safety meeting.

At the top of Beacon Hill heading into Fort McMurray the crew gathers for another tailgate safety meeting.

“Is it cold enough for you?” Chris Waddell, Premay’s Transport Supervisor, smiles clapping his gloves together. “We’ve had a couple of cold days at Grassland where we had to shut down because it was too cold to lift the power lines. But we’re here now and checked over the load and trailers and we’re ready to go again.”

The descent into Fort McMurray requires a lot of braking. The brakes on the Scheurle hydraulic platform trailers squeak under the load on the way down. It is slow going and it has to be. Even though there is grit and sand on the road it is still slippery.

The bridge that crosses the Athabasca River in Fort McMurray has seven long spans. UMA in Edmonton were hired to calculate the forces applied to the bridge by the Coker transport and are on site to supervise the crossing. The careful planning pays off as the Coker crosses without a hitch.

Don Uchytil is Director of Operations and he predominantly runs ahead of the load in his pick-up checking the road conditions.

“For example the steepest hill on the way to Suncor is locally known as “Super Test”, Don explains. “I’m checking to see if we need the road ploughed and getting it sanded before the load gets to it. We need all seven prime movers hooked up for this hill.”

“Stopping up here is not an option,” Don fervently remarks.

Again, it is slow going for the seven C500 Kenworths. Their Caterpillar engines really working hard even with the Joey box in extra low. But sure enough the load makes it to the summit.

Again, it is slow going for the seven C500 Kenworths. Their Caterpillar engines really working hard even with the Joey box in extra low. But sure enough the load makes it to the summit.

After thirteen days on the road and some 800 kilometers the Coker arrives safely at Suncor’s Tar Island plant though the careful planning and expertise of the Premay crew.

Premay is a subsidiary of Mullen Transportation Inc. and specialises in heavy haulage for western Canada’s oil and gas industry. Its transport division shift and move giant equipment in both on highway (up to 800 tonnes) and off-road applications (up to 1400 tonnes) to production locations such as Alberta’s tar sands, which accounts for about half of Premay’s heavy hauling business. A separate division loads, hauls and “strings,” or lays down, pipe for oil and gas pipelines.

“A 200-ton load is every day work for us,” Brett added, who joined the company as a truck driver in 1978 when it had just three company trucks and 14 leased truck operators.

Premay’s fleet of Kenworth C500s is equipped with Caterpillar 550-horsepower engines driven through Allison automatic transmissions. The company also operates Kenworth T600s, T800s and W900s for “lighter work,” Brett explained. All told the company runs 41 Kenworth tractors.

Why Kenworth? “Kenworth gives us the ideal combination of quality and reliability,” Brett volunteered. “We work with the engineering people at Kenworth to build these trucks from the ground up. We are impressed with the quality that Kenworth provides in designing and building these trucks for Premay.

“When we put our Kenworths on the ground, our drivers appreciate everything about them, from the cab comforts to their authoritative drivability. And our mechanics are impressed with the ease of servicing the trucks in the shop,” Brett revealed.

“We view our trucks as 10 to 15-year tools and Kenworth is the most reliable tool you can find in the industry,” Brett Harris concluded.